Fluke - Book Review

Contents

This blog post is a quick summary of the book “Fluke”, written by Brian Klass.I haven’t had time to read a book in the last 30 days because I was tied up traveling for work and building a few apps. Thanks to a hiatus in my project delivery work, I have managed to read this book. Here is a brief summary of the book

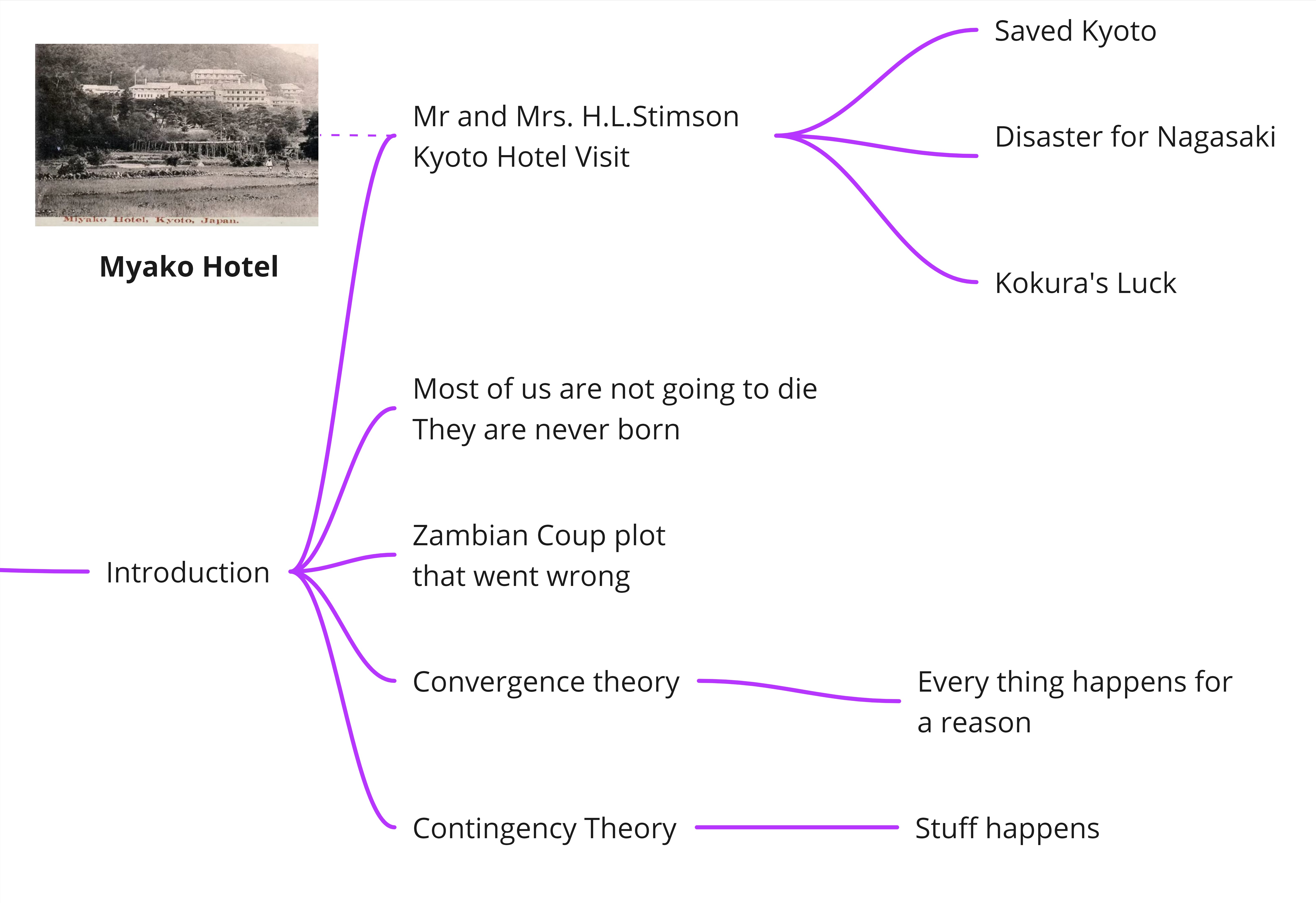

Introduction

I loved the intro chapter where the author connects a fluke event, i.e. a couple visiting Kyoto restaurant to significant ways in which atomic bombing history in Japan changed forever. Strange yet true - fluke events that occur randomly have a significant effect on how we see the world unfolds. How much ever we try to fit our thinking in to a world view that world is driven by neat cause and effect linear thinking framework, the author provides enough meat in the intro chapter to make the reader look forward to the rest of the book that posits that world is a contingent convergence world.

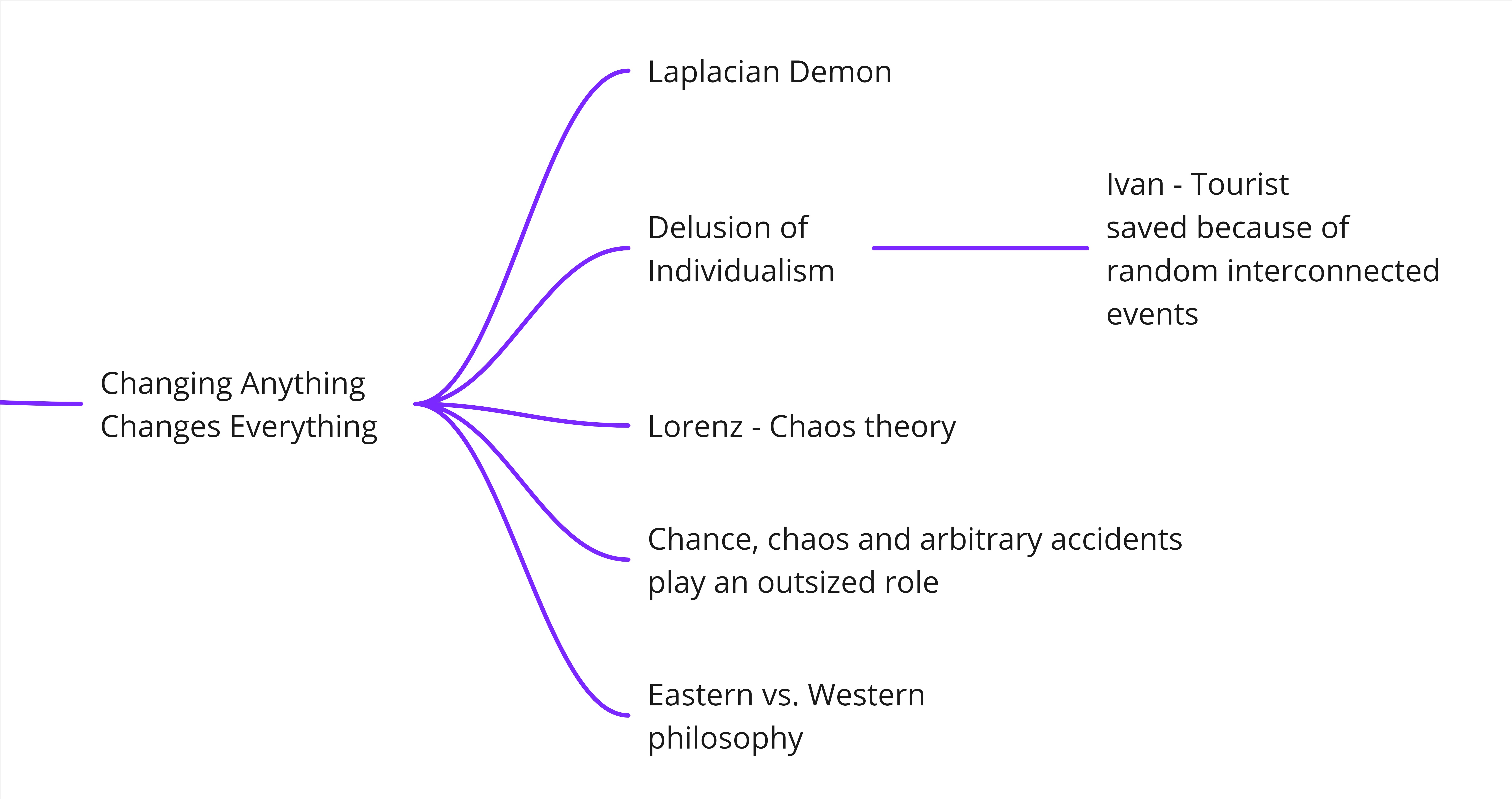

Changing Anything Changes Everything

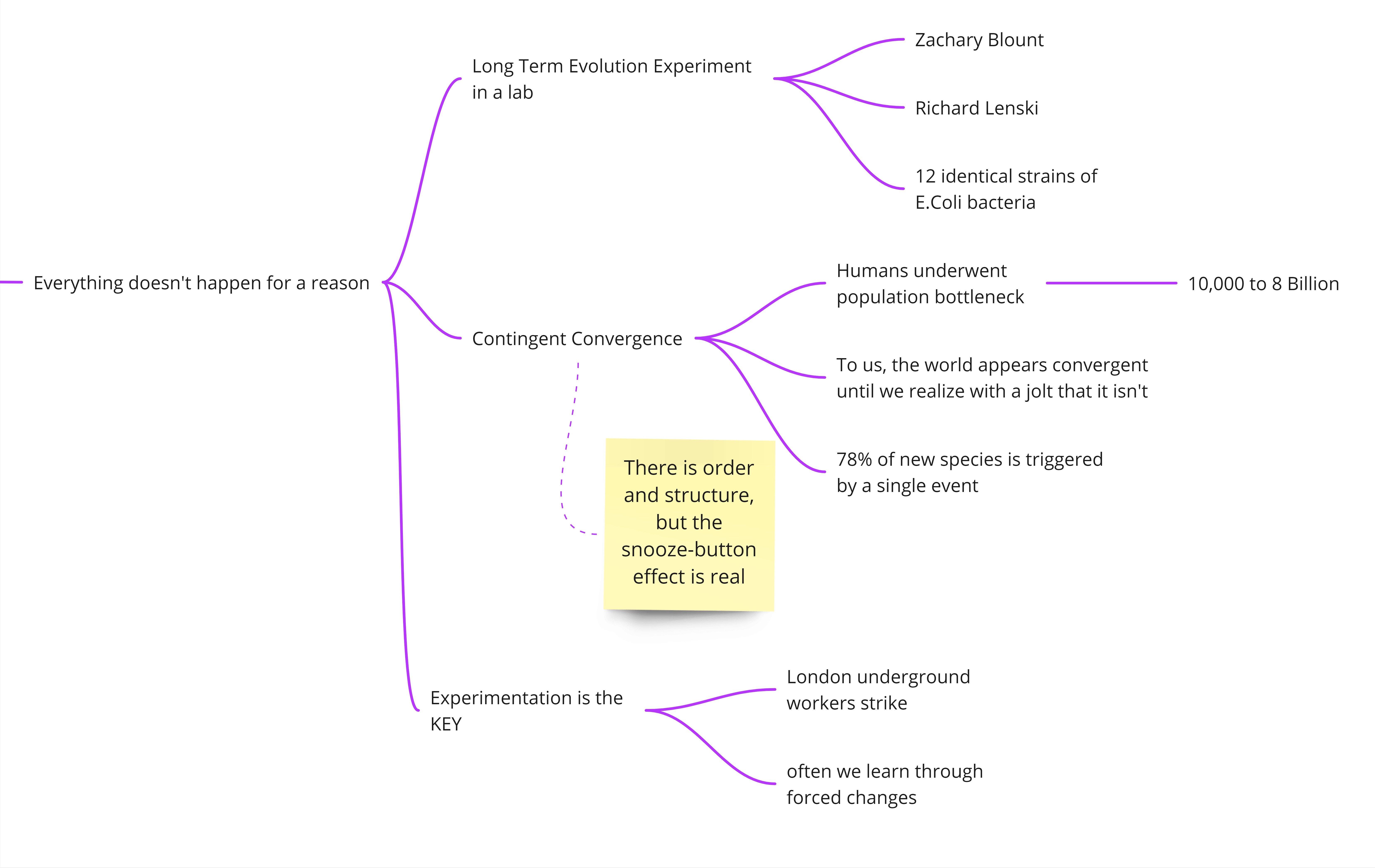

Everything doesnt happen for a reason

The chapter is all about arguing the notion that our world is “Contingent convergence”. Most of the world seems to be moving in an organized manner until a seemingly random event changes the course of the world. The chapter goes in to the details of a lab experiment involving a E.coli bacteria to illustrate the finding that rare and random events have unimaginable effects on the species on an evolutionary scale.

Multiple examples are provided in the chapter that say that our world moves in largely smooth manner until a random event changes the course of our lives. Here are a list of examples provided to reinforce the stance

- 2 Billion years ago, all living beings on Earth were single celled organisms until a single bacterium bumped into the cell and ended up inside it. That bacterium evolved into mitochondrion, the powerhouse of our cells. Every future species of complex life owes its existence to this unexpected microbial merger.

- Humans don’t lay eggs can be traced to a single event that happened millions of years ago

- Appearance of marmorkrebs in Madagascar

- Downplay the role of luck in the success of an individual

- Evolutionary biology: Organisms mutate and random variations accumulate, which creates the genetic building blocks for a trial and error approach for solving problems

After going through the chapter, one definitely might starts paying attention to small actions and not brushing out those actions as they don’t matter in the long run. Every action of yours along with millions of actions of ancestors and millions of actions of fellow beings seem to open up the possibilities and paths in our lives. This means our behaviors and actions, as insignificant as they might appear, might change the course of our lives. This is also a liberating feeling. We might think that our live is more or less stable and our future potential to do things has a ceiling. Not really. If you subscribe to the contingent convergence view of the world, the possibilities at any age are endless.

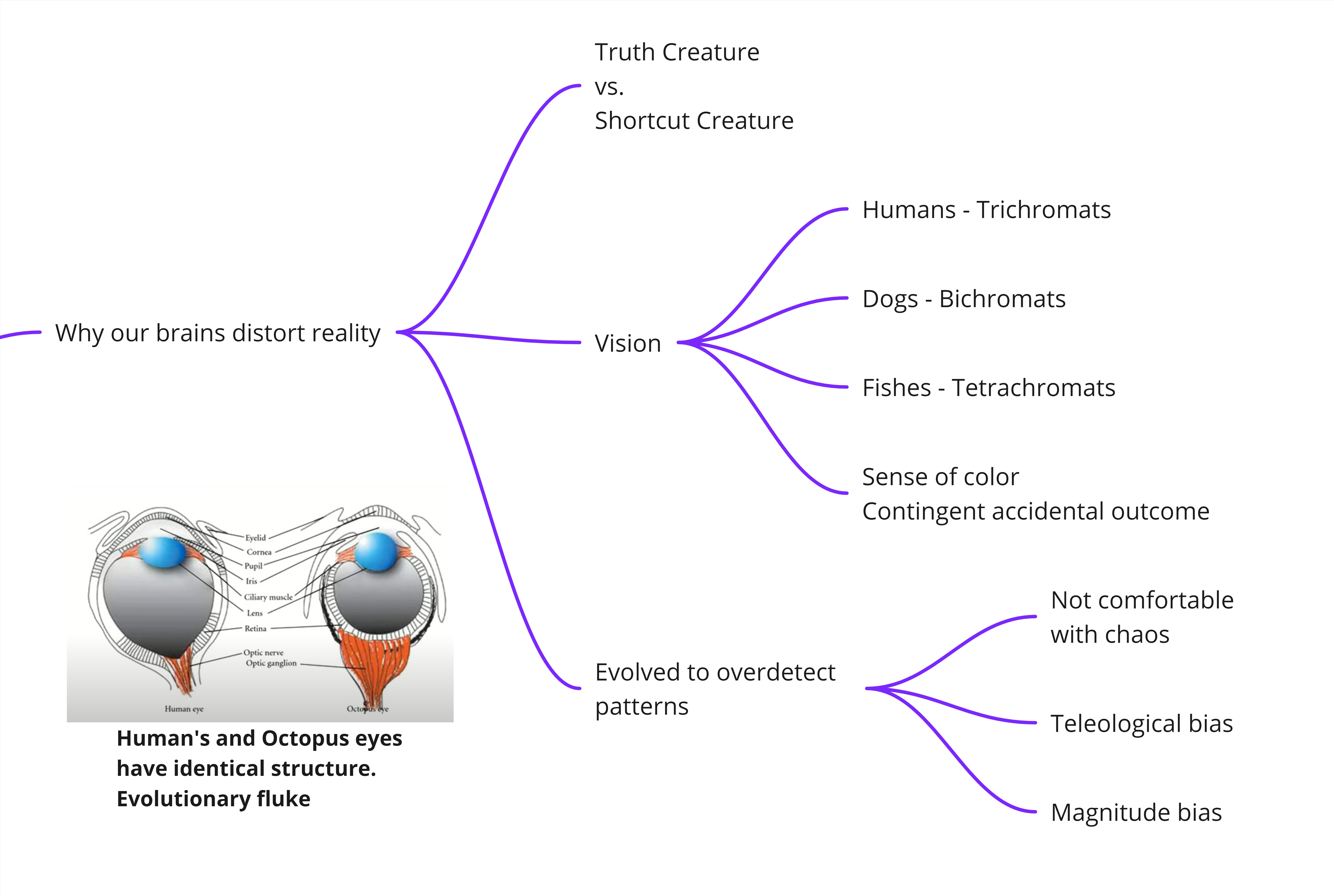

Why our brains distort reality

The author makes the point that we have many inherent biases when we see the world, and these biases make us lean towards “stuff happens for a reason” stance even though it might not be otherwise.

Our brains have evolved to over-detect patterns, i.e. commit more false positives than false negatives. Failing to detect a rustle made by a wild animal in the jungle ended up with a catastrophe. There are umpteen examples that show that humans are not comfortable with chaos and ends up weaving up patterns, narratives even when the events happen randomly. One such evolutionary fluke relates to the color detection capabilities of humans, dogs, whales, fishes and other creatures. We are trichromats, i.e. we can detect red-blue-green colors whereas dogs can detect blue-green colors whereas fishes detect four colors and are called tetrachromatic.

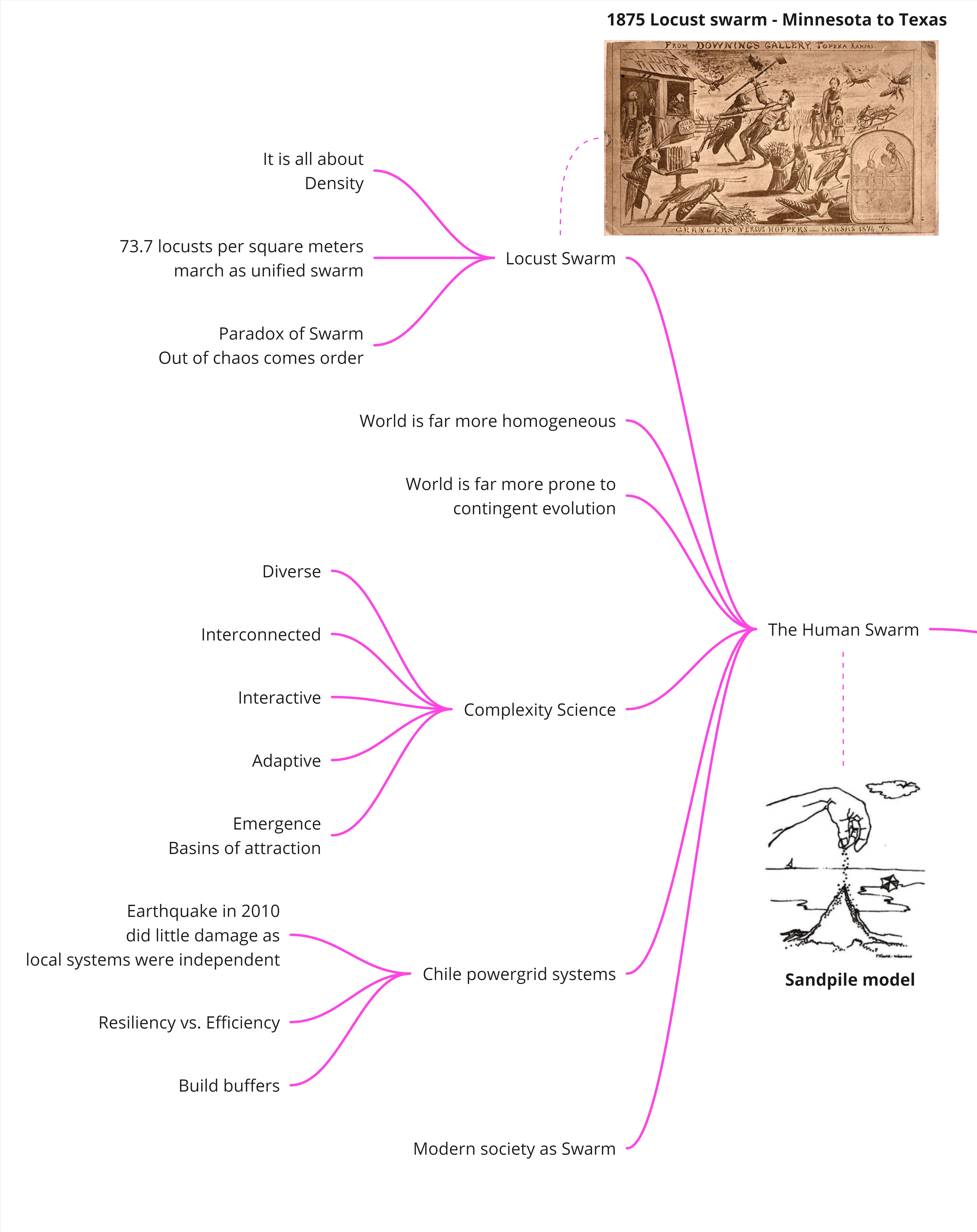

The Human Swarm

The author gives the example of locust swarm of 1875 that destroyed the farms from Minnesota to Texas. The swarm was so powerful that nothing could prevent it from destroying the fertile plains. Do locusts work in unison and fly together ? Mostly individual locusts are pretty harmless until the density per square meters touches 73, when they start moving as a swarm. Until the density hits the cricual number, the swarms move in an uncoordinated manner and are pretty harmless. The author compares the locust swarm to our modern society where each one of us is becoming more homogeneous than ever. However a tiny event can cause massive behavioral changes like Covid.

Our focus on hyper efficient and hyper optimized world is leading to a situation where we don’t have buffers in many systems that we are designing. Any unexpected shock creates chaos and hence the whole system ends up in chaos. Powergrid in Chile is a good counter example of a system that has been built to withstand earthquakes by baking in redundancy.

The takeaway of this chapter is that there are small events that can cause disproportionate effects and these small events occur frequently and are often unpredictable in their consequences.

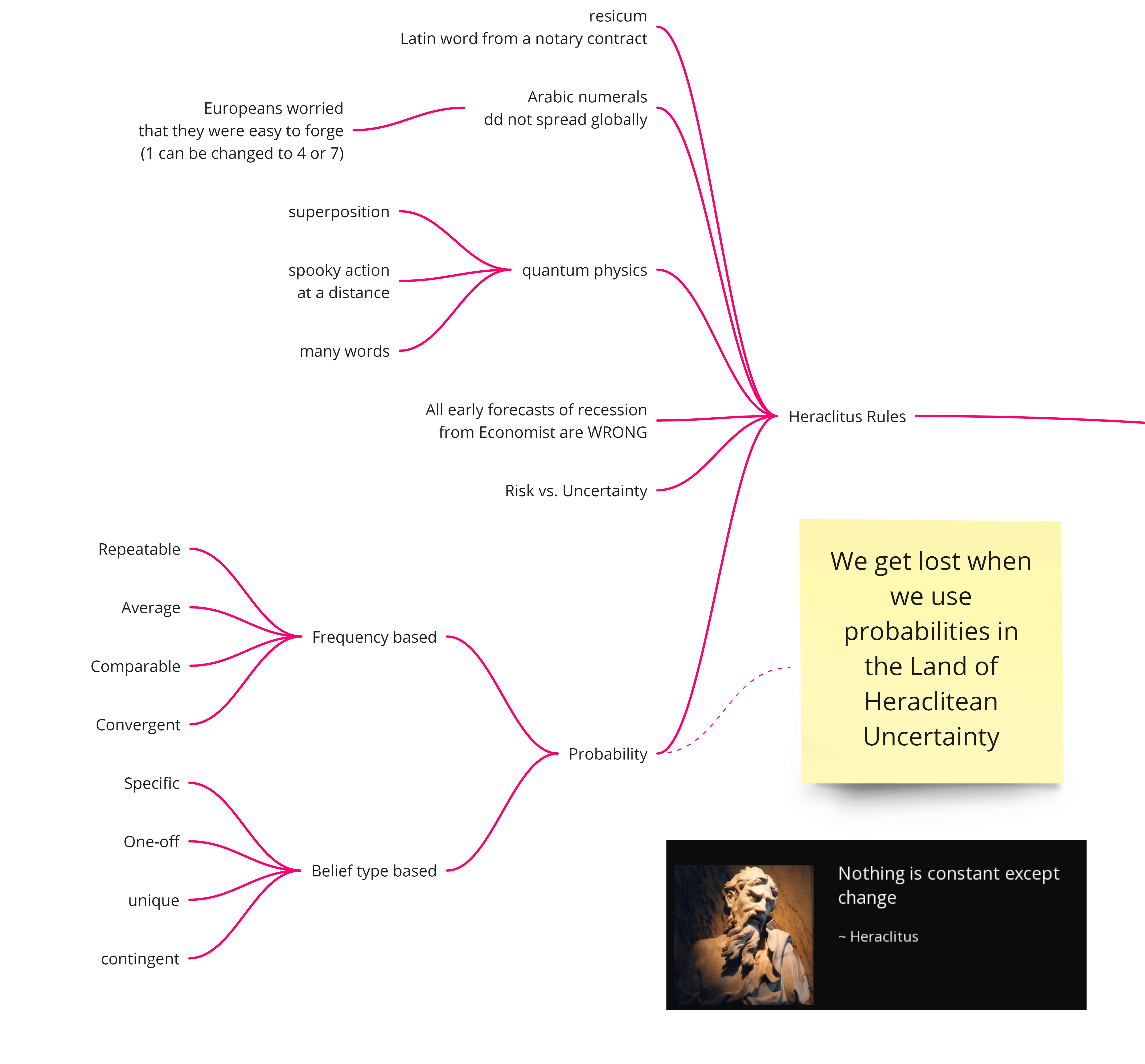

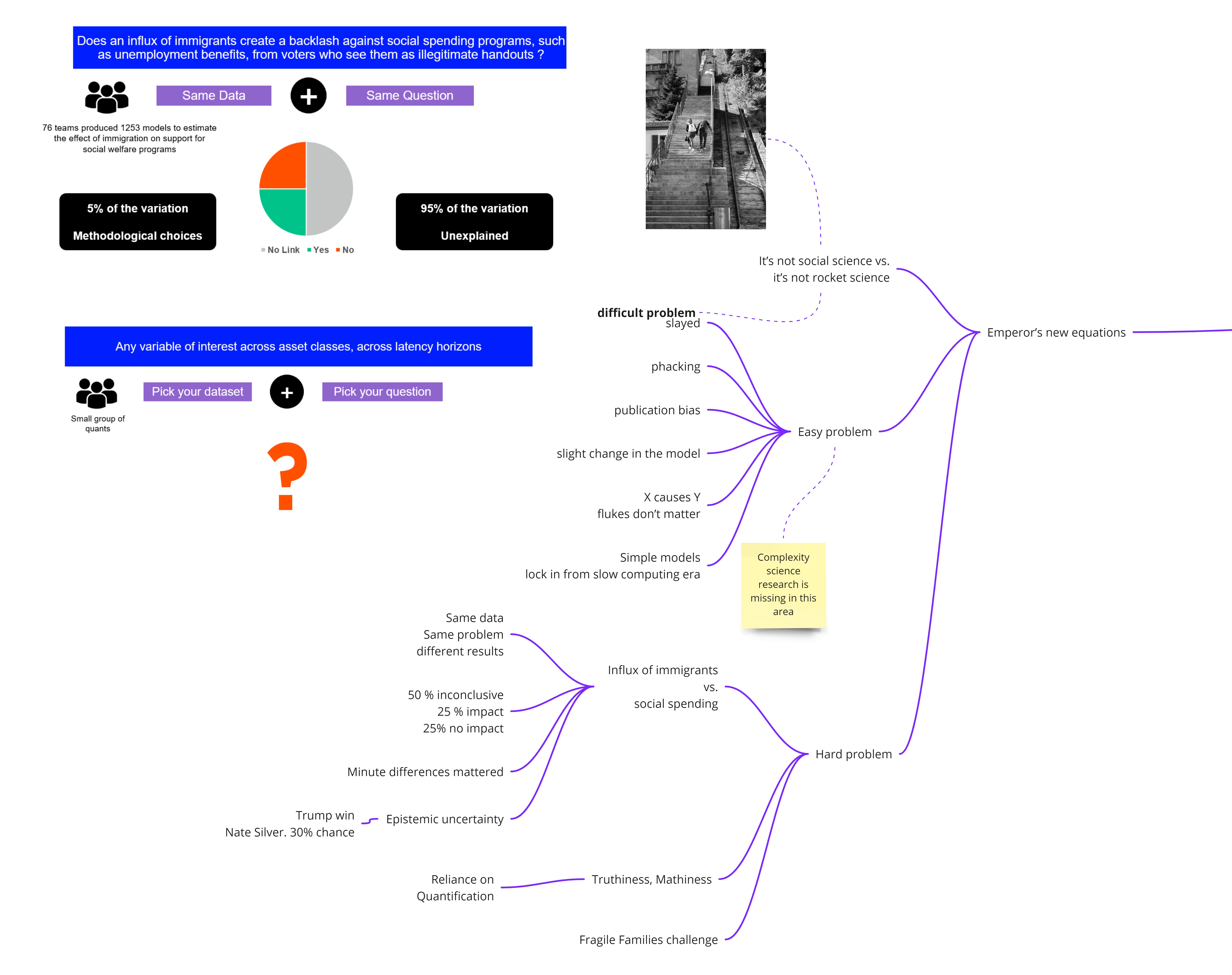

Heraclitus rules

The message of this chapter is super familiar with any one who has worked with frequentist and Bayesian stats. Even though we are familiar with these tools and we use it more than needed situations, we are lulled in to a false sense of security using the probabilistic output. The chapter makes a case that both these type of probabilistic models fall apart in our world that is dominated by black swans and flukes. Yes, one can use these models in deterministic worlds like recommendation engines, movie recommendations etc. But when it comes to predictions where the payoff is outsized as compared to the probability of the occurrence, most of the probabilistic models fail.

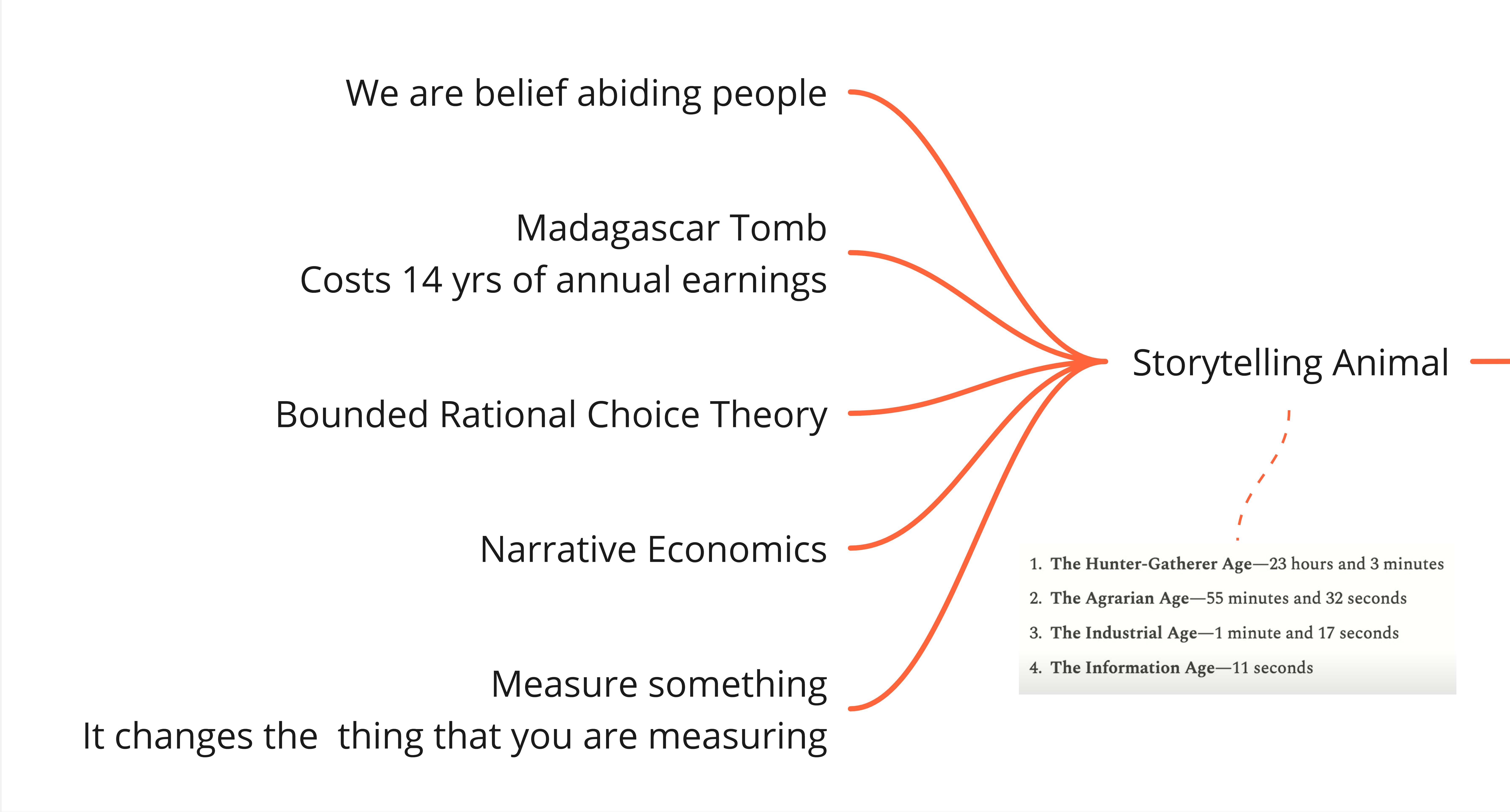

The Storytelling Animal

This chapter delves in why as we act as we do and says that narrative drives events more than the objective reality of the world. Humans might appear as rational utility maximizers in the textbooks but in reality make decisions that have a ton of biases.

Humans, unlike molecules in a gas or comets in an orbit, are self-aware and self-reflexive. Our thoughts are also influenced by sensory perceptions, experiences and the thoughts of other thinking, self-reflective beings, all moderated by culture, norms, institutions and religions. That level of complexity simply doesn’t exist in a liter of gas.

Our brains are so attuned to narrative that we will connect the dots into a story even when the dots aren’t connected, which is called narrative bias.

The story telling mind is allergic to uncertainty, randomness, and coincidence. It is addicted to meaning

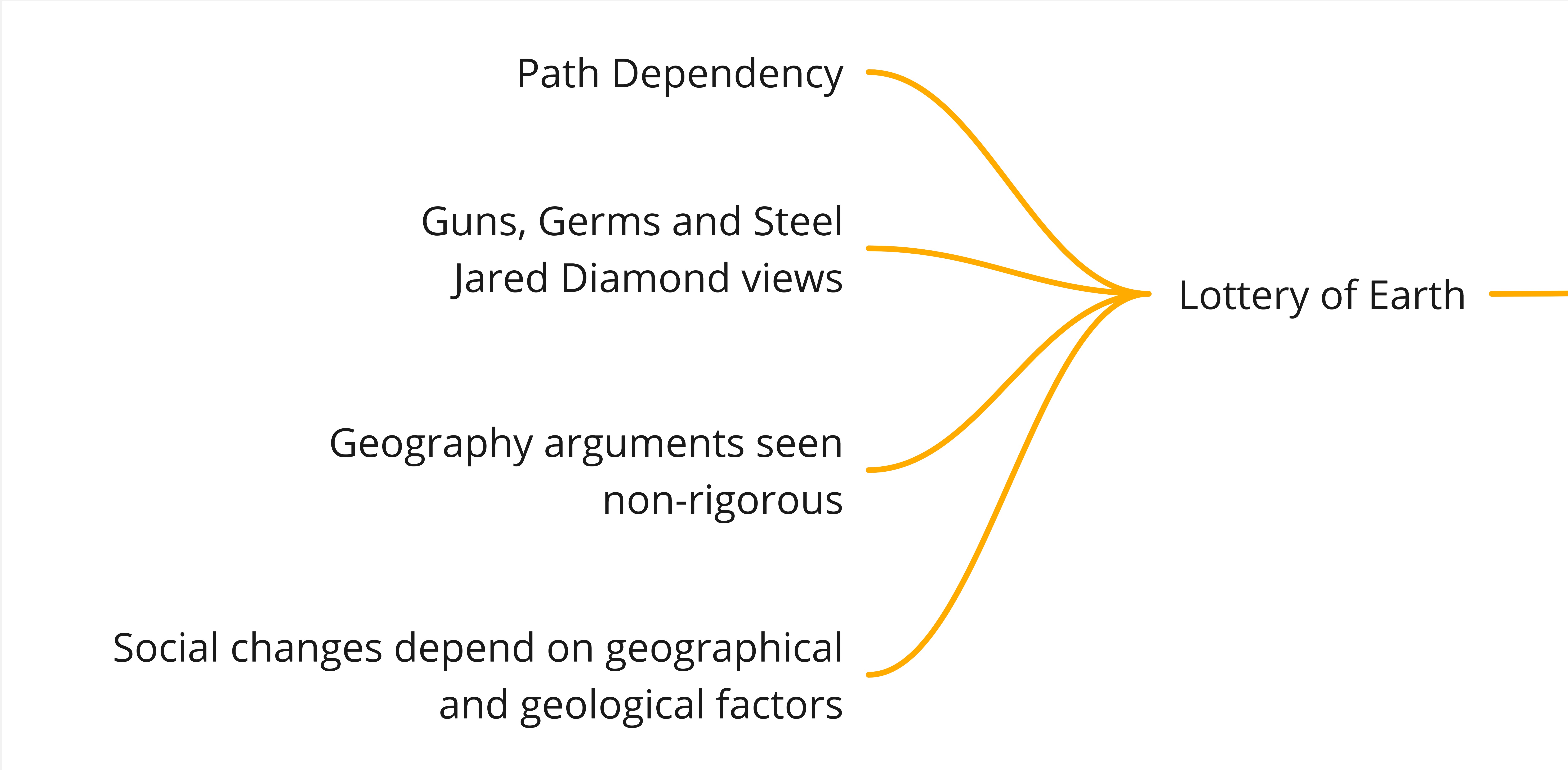

The Lottery of Earth

The author makes a case of the importance of “where” something happens, in the way our world evolves. Some of the examples mentioned in this chapter are

- Pine Tree Riot as a catalyst for Boston Tea Party, and by extension, the Revolutionary War and American independence

- Evolutionary pressure to get smarter also likely become more intense due to drastic, unexpected shifts in the climate

- Ancient empires were guided by hidden fault lines below the surface of the earth

- Human history was diverted by the shape and orientation of the continents - an idea known as the continental axis theory

Everyone is a Butterfly

Does it matter who does the discovery of a scientific principle ? Will it anyways be discovered and propagated ? The author gives several examples where the actual person doing the discovery was key in the idea and principles getting propagated in the scientific community.

The author traces the various approaches that were used to understanding history. For centuries, it was broadly accepted that key individuals determine history, called the Great Man Theory. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, historians, philosophers and economists pushed back hard against the Great Man view. In the 1920s and 1930s, the Annales school of history emerged in France, founded by a group of scholars who looked to understand social change by analyzing long-term society wide trends rather than specific individuals or key events.

David Ruelle, a Belgian mathematical physicist, offers a useful thought experiment to show the limits of this kind of thinking. Imagine placing a single flea in the middle of a checkerboard. Probability theory could effectively predict, on average, how often that flea will leap to any specific square on the board. So far, so good.

Now, consider adding sixty-three additional fleas to a sixty-four-square checkerboard, and affixing a name tag to each one: there’s Rick the flea, Ellie, Joe, Ann, Caspian, Anthony, and so on. Trying to accurately predict where Rick or Ellie will be at any given time is likely to be impossible. There are too many potential combinations with sixty-four fleas on sixty-four squares. However, social science models will be exceptionally good at predicting, based on behavior over time, how the fleas will generally arrange themselves on the checkerboard—the space between them, their rate of movement, the average height of their leaps, and so forth. These kinds of problems—such as predicting traffic flows, where it doesn’t matter as much which specific driver is on the road—are perfectly suited for our research tools.

Now, what if just one flea—let’s call him Nigel—is a cannibal? Suddenly, any attempt to predict or understand the dynamics of that checkerboard based on averages or equilibriums are no longer useful because the individuals are no longer interchangeable. The fleas will flee from Nigel. Next, imagine if every flea is a bit idiosyncratic. One flea, Barbara, will leap off the board completely if she ends up within two squares of Nigel. Two others, Paul and James, refuse to move, no matter what. One flea, Kelsey, prefers the corners of the board, so she’ll stay put if she ends up in a corner square. To make matters more complex, these behaviors change over time, as the fleas learn, adapt, and develop new preferences based on their experiences. Suddenly, the initial conditions of the flea’s positions matter enormously. Every time you rerun the experiment, something completely different happens.

Yet, the study of humans, which are vastly more complex than fleas, too often pretends that the specific people don’t matter much.

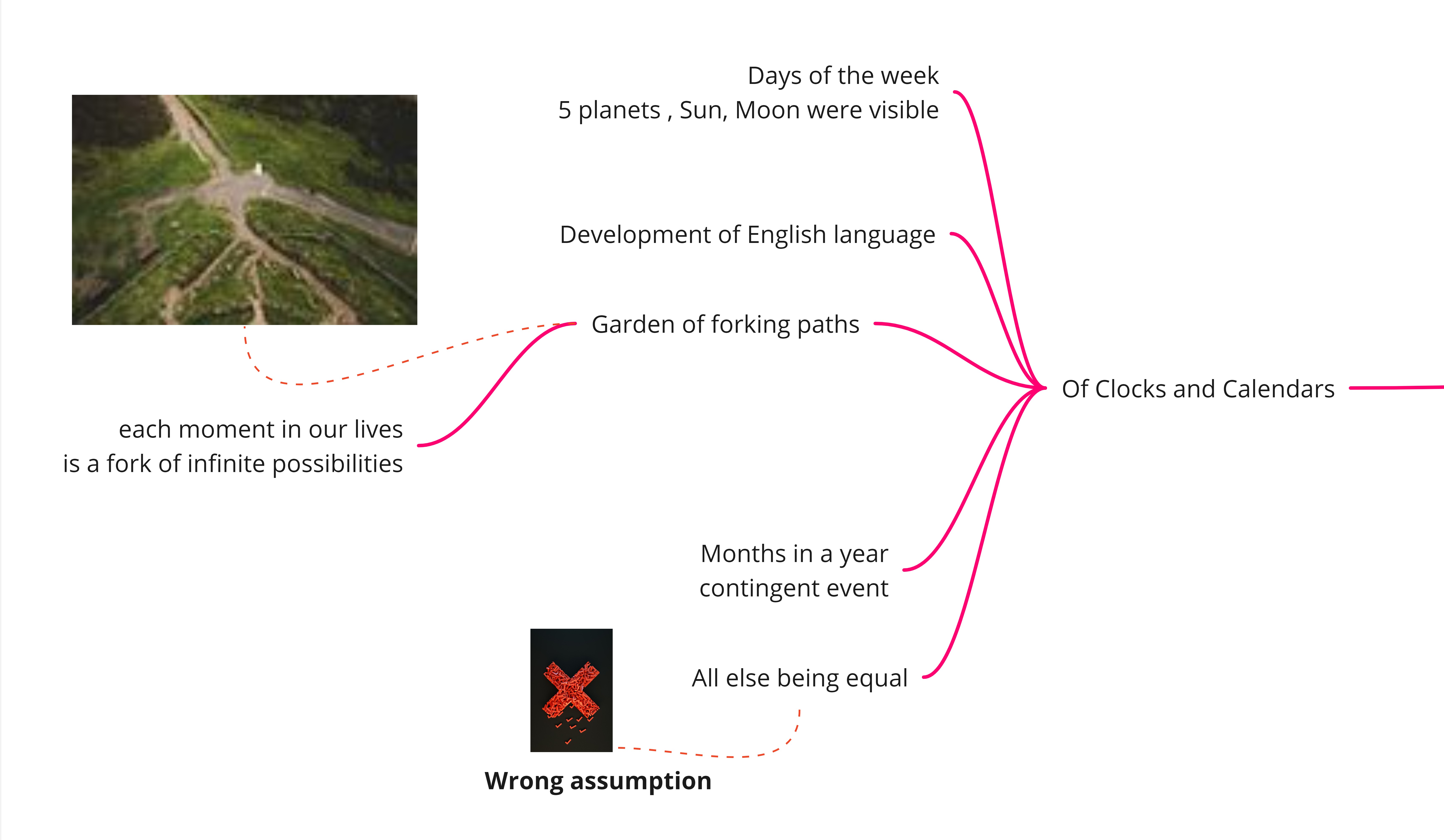

Of Clocks and Calendars

Emperors new equation

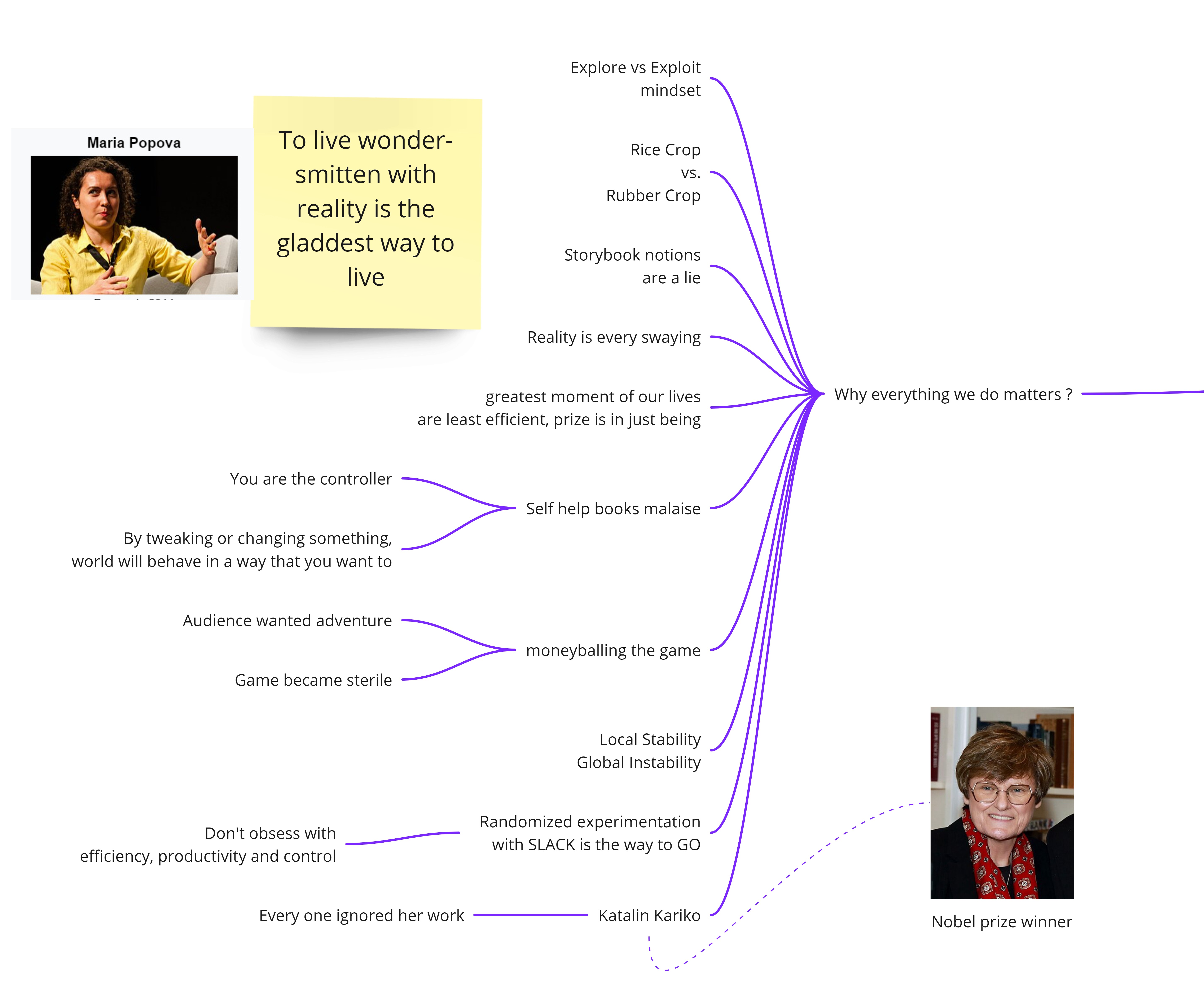

Why everything we do matters

Loved the concluding chapter of the book, in which author reiterates some of our biases such as narrative fallacy, pattern over-detection, magnitude bias for attributing causation etc. and offers a rather fresh perspective on how to go about living one’s life. The chapter opens with a beautiful quote from essayist Maria Popova

To live wonder-smitten with reality is the gladdest way to live

There is a nice analogy of “Rice crop vs Rubber crop” mentioned in the chapter to distinguish between the situations or contexts in which things are by nature random and situations in which things happen in a methodical way. Most of the world falls in “Rice crop” category where a healthy exploration should proceed before exploitation. The author also takes a dig at the self help books that propose a philosophy that by tweaking one’s behavior, one’s thoughts and actions, universe can be made to behave the way one wants. This is total sham as the world is driven by a ton of flukes, individual actions and very often we try to attribute the world’s events to a few causes, just because we are unable to comprehend the world and model the world.

We are living in a world where there is local stability - at any given moment one can reasonably guess what a urban city dweller might be doing, wearing, hearing etc. the urban city. In that sense there is stability at a local level but very often there are uncertain fluke events that rupture the fabric of the entire world leading to global instability. One of the ways to get out this situation is to strive for resiliency than efficiency. By building buffers in to our individual and collective lives, we can avoid catastrophes in our lives.

Randomization and a healthy dose of slack is what is needed in everyone’s life.

Takeaway

There are so many interesting takeaways from this book and am listing a few

- Our world is contingent convergent

- Every event that occurs has chance to influence society in a profound way, that is unknowable a the time the event happens

- We control nothing but influence everything

- Why do social science academics focus on creating causal models that are brittle ? suffers from replication bias, p-hacking, publication bias

- Sandpile model as a visual image for checking magnitude bias

- It is not necessary that big causes give rise to big events

- Building redundancy in the system is more important than making over-efficient systems

- Experimentation is the key in this ever changing world. Instead of worrying about causal models, may be it is better to create stuff and then pay attention to outcomes, get a rough sense of feedback to the events and keep iterating

- Our world is becoming locally stable and globally unstable. It was locally unstable and globally stable in the hunter gatherer era, agrarian era and industrial revolution era

- London Tube commuters and forced experimentation situation

- Human brains are wired to weave stories and detect patterns even when there are none

- Geography can play an out-sized factor in many things that happen, even though modelers might never want to consider it

- Time scale - We have so many biases that are wired in our brains because of

the vast time that we have spent across various ages. Information age is

vastly different

- Hunter gatherer age - 23 hours and 3 minutes

- Agrarian age - 55 minutes and 32 seconds

- Industrial age - 1 minute and 17 seconds

- Information age - 11 seconds

- Accept causal and radical uncertainty

- Avoid catastrophe

- Way to talk about contingent vs convergence event - Snooze button

- We remove the noise in the model, We remove the outliers. But in social science and probably other domains, they matter a LOT

- We cannot ignore the noise and only focus on Signal

- Traditionally, our ideas tied to elegant order. Models were too simple and took a few main variables. It might work in certain types of world. But it will not work in most situations

Absolutely loved the book. I am sure that I will reread this book at some point in the future.